Are camping setback regulations the most effective approach to resource protection?

Most hikers, riders, and equestrians who spend time out on the Tahoe Rim Trail strive to enjoy their experience while still following the rules and regulations put in place to protect the trail, natural and cultural resources, and the experiences of their fellow trail users. Yet when it comes to choosing a campsite, and particularly one near water, best intentions often fail to produce a positive outcome.

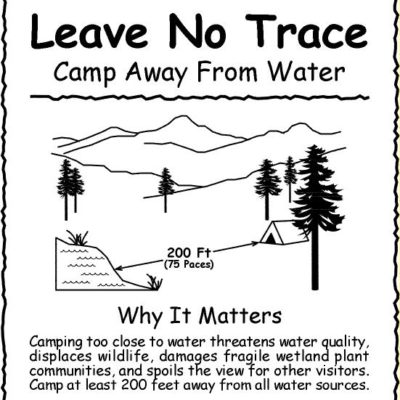

Simple messages like the one above are easy to digest but lack valuable nuance.

For more than 20 years the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics has consistently recommended camping a minimum of 200 feet from any water source. This recommendation isn’t wrong, but it also lacks nuance and context that may be essential for gaining voluntary compliance. Surveys of overnight campers consistently report the strong draw of camping near water for its utility, scenic beauty, fishing and swimming opportunities, relaxing sounds, and opportunities to see wildlife and explore shorelines. A strong rationale against camping right on the water is needed to overcome these desires, and simply providing a setback distance without explaining why it is given is not convincing enough for some. In addition, the LNT recommendation may not be an accurate setback for mitigating the negative effects that can arise from camping very close to water. These effects include threats to vegetation, soils, water quality, cultural/historic sites, wildlife, rare or sensitive species, and social experiences. For example, in locations such as arid plateaus, 200 feet may not be far enough to ensure wildlife have adequate access to isolated water sources. Conversely, in situations where topography drains a campsite away from a nearby water source, 200 feet may be much farther than is necessary to avoid water contamination.

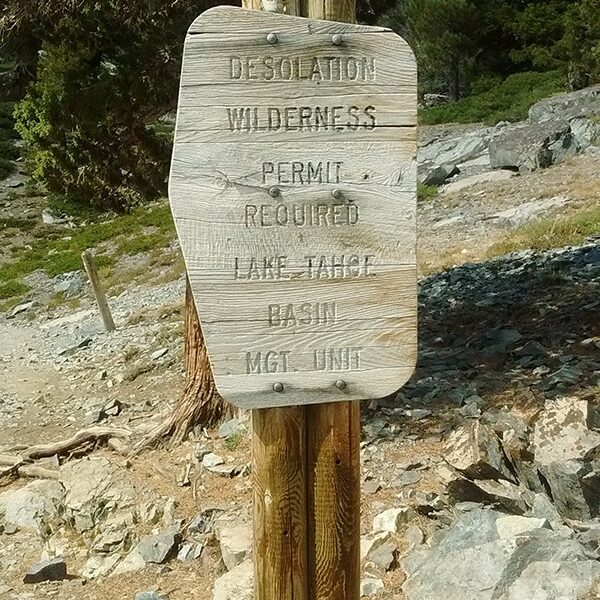

To further complicate the matter, the LNT setback recommendation is not consistently communicated by management agencies. Recent research has shown that recommendations for camping setbacks from water in Forest Service Wilderness areas range from 50 to 1,320 feet, with 100 feet as the most common. Regulations are slightly clearer around the Tahoe Basin. In Desolation Wilderness, the Eldorado National Forest and the LTBMU require campers to stay 100-200 feet away from water (depending on the source consulted, though in one case different distances are provided in the same document), but require washing and waste deposition to take place at least 200 feet away. In some specific locations the setback jumps to 500 feet for camping. Most Forest Service webpages related to other special management areas where camping is allowed, such as Meiss Country and Mt. Rose Wilderness, don’t offer any guidance on the subject but simply state that dispersed camping is allowed. Conflicting or absent messaging isn’t surprising, but it is discouraging, particularly when scientific evidence has yielded strong recommendations that can significantly reduce unwanted camping impacts near waterbodies.

The current camping regulations on the Tahoe Rim Trail allow for dispersed camping within 300 feet of the trail in most locations, including areas where that buffer contains water. Dispersed camping is often the preferred regulation because it does not require active management (ie. money, staff time, and expertise) and because it doesn’t impose restrictions on users, who generally enjoy the freedom associated with spending time outdoors. However, when visitors are allowed to choose campsites in areas with water they tend to both exhibit universally poor compliance with recommended or required camping setbacks and to create campsites that are unnecessarily large and excessive in number. This is clearly the case in some locations around the trail including Star Lake, Round Lake, Showers Lake, Lake Richardson, and most if not all of the alpine lakes the trail passes by in Desolation Wilderness. But the solution is not to simply better educate and enforce the LNT recommended setback, or to attempt to restore unsustainable sites. Site restoration is chronically ineffective unless coupled with creating new, sustainable sites nearby that are easily found and attractive to campers. Furthermore, in some cases camping setbacks are counter-productive. Without an on-site caretaker to ensure 100% compliance, setbacks often result in some people ignoring or misinterpreting the rules, thereby continuing to use and create sites right next to the water, while others try to follow the rules and create new campsites farther away. Thus, the areal extent of disturbance is actually increased.

Sites like this one on the shore of Star Lake resist restoration efforts as no viable alternative approach to camping at the lake has been enacted.

A lack of campsite management at Richardson Lake has resulting in the entire north shore becoming one uninterrupted camping area.

If education, enforcement, and restoration on their own are ineffective, what can be done? Luckily, there are other options. The most attractive and proven approach is known as containment or designated site camping. In this approach (which is already in place near Lake of the Woods, Grouse, Hemlock, and Eagle lakes in Desolation Wilderness) campsites in sustainable locations are identified or created and then marked so they are obvious to campers. Visitors are asked to stay only at these sites, which are not reserved but are available on a first-come, first-serve basis (overnight Desolation Wilderness permits specify a zone, not an individual site, even near the lakes mentioned above). Periodic monitoring helps determine if additional sites are required to meet demand, and restoration on unsustainable sites has a better chance for success. Though visitors’ freedom to choose an overnight site is somewhat limited, research suggests that designated site camping is widely acceptable among recreationalists and is vastly preferred over camping prohibitions. In addition, this strategy does not require campers to interpret unclear or conflicting setback messaging or to be able to determine how far 200 feet actually is on the ground. With a containment camping system, even campers who have no knowledge of Leave No Trace can be expected to leave minimal and contained impacts. The system need only be put in place near water, thus leaving the vast majority of land along the trail open for dispersed camping unregulated.

Containment camping regulations are already in place in some areas of Desolation Wilderness.

So why don’t we already have such a system in place in locations where it is clear that campsite impacts are large and increasing? The answer is complicated, but the main drivers are lack of knowledge, resources, and time on the part of agency land managers. While organizations like the TRTA can implement projects that would bring designated campsite systems to those places along the trail that need it most, we can’t do so without the green light from land managers. To put this issue on their radar we need the public’s help in raising awareness of the problem and in insisting on adequate and appropriate stewardship of areas near water bodies that are popular for camping. Please let us know your thoughts on the subject so we can get more traction on this issue and begin implementing meaningful change.

Works Consulted:

Cole. D.N. 1981. Managing ecological impacts at wilderness campsites: An evaluation of techniques. Journal of Forestry 79: 86-89.

Eagleston, H. , and J.L. Marion. 2017. Sustainable campsite management in protected areas: A study of long-term ecological changes on campsites in Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, Minnesota USA. Journal for Nature Conservation 37: 73-82.

Marion, J. L., J. Wimpey, B. Lawhon. 2018. Conflicting messages about camping near waterbodies in wilderness: A review of the scientific basis and need for flexibility. International Journal of Wilderness (24)2. 12 p.

Reid, S.E. and J.L. Marion. 2004. Effectiveness of a confinement strategy for reducing campsite impacts in Shenandoah National Park. Environmental Conservation 31(4): 274-282.